Working Title: The Illusion of Social Responsibility,

The Production of Coca-Cola’s Corporate Image in Chile

Proposed Table of Contents (need to edit titles)

Acknowledgments

Abstract

Introduction: Theory and Methods for Analyzing Coca-Cola Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Campaigns

Chapter 1: The Coca-Cola System

Chapter 2: Coca-Cola’s Marketing of CSR

Chapter 3: Case Studies: CSR Campaigns in Chile and Colombia

Conclusion: The Production of the Socially Responsible Image as Part of a Global Strategy

Appendices

Bibliography

Introduction

In August of 1990, the Coca-Cola Company opened The World of Coca-Cola, a corporate museum dedicated to displaying a polished version of the Company’s history through a collection of antique bottles, memorabilia, advertisements, and corporate archives (see exhibit 1). One of the first displays to welcome visitors is a “spectacular behemoth carrying overhead apparently endless lines of Coca-Cola bottles… the relentless continuity of this ‘Bottling Fantasy’ by Jan Bochenek is startling and absorbing” (Harris 154). Outside the museum hangs a thirty-foot globe containing a twenty-six foot neon, rotating Coca-Cola sign; a gaudy and overbearing symbol of Coca-Cola’s domination and presence in over 200 countries worldwide (Harris 154). Yet, there is something inherently problematic with Coca-Cola’s historical account. As Neil Harris points out, “the Coke story is told absolutely without tension or conflict… Coca-Cola’s impact on the world is projected as problem-free” (157). It is as if Coca-Cola had placed over 100 years of history into a black box and the end result was a story where Coca-Cola was always the hero, always welcome, always a friend. The museum is more of a fantasyland, a refashioned hip interpretation of corporate history, the way Coca-Cola would like to view itself and be viewed by the world.

Although The World of Coca-Cola is only one site of Coca-Cola advertising, it is emblematic of a larger marketing strategy; one that attempts to process complex cultural, political and economic differences into a unified narrative. When Coca-Cola introduced the “Always Coca-Cola” campaign in 1993 it ran twenty-seven different commercial designs. Even though each design was different, the final message was the same: Always Coca-Cola. As Mark Pendergrast explains, “Coke has created ‘patterned advertising’ which, with little or no modification, can appeal to any culture in the world. The Coke message has universal appeal- by drinking this product, you will be self-assured, happy, popular, sexy, youthful…” (464). Aside from the obvious message of: Buy Coca-Cola!, what other intended or unintended messages come across through the stories told in Coke ads? What cultural values do they enforce or reject?

Antonio Gramsci pointed to the coordination of politics, economics, intellect, and morals in establishing and maintaining hegemony. As Gavin Smith explains, hegemony is used "to refer to the complex way in which power infuses various components of the social world" (216). The relationship between power and hegemony is broadly conceived by social scientists, yet Gramsci names a few institutions which were instrumental in acquiring hegemony in Italy during the early 1900s, including the church and the public schooling system. He also draws attention to the economy as a potential site for the consolidation of power. Smith states,

"Gramsci identified a very particular compact for securing social order between corporations and the state: “an intensification of exploitation achieved through new forms of management and corporatist strategies, and expansion of state intervention in the economy and society” (225).

Tracing the relationship between state institutions and corporations provides an entry point to examine how hegemony is secured through relationships between educational, state, and economic institutions, as well as the media.

In The Political Psyche, Andrew Samuels outlines two basic locations where political and economic power can be secured which he labels the “public and private dimensions” (4). Within the public dimension he defines economic and political power as “[the] control of processes of information and representation to serve the interests of the powerful as well as the use of physical force and possession of vital resources such as land, food, water or oil” (3). Within the private dimension political power is reflected in “struggles over agency, meaning the ability to choose freely whether to act and what action to take in a given situation” (3). Samuels suggests analyzing the interplay between these two dimensions as a way to get an in depth understanding of how power operates within a society. Multinational corporations provide an interesting case study because they are commercial entities operating in the public sphere. Yet, through various forms of advertising they can virtually shake off their corporate bodies and step into the private sphere with a kind of disembodied corporate image. Within the more intimate setting of the private sphere, corporations can operate in a more flexible manner and potentially influence the values and beliefs of individuals.

The Coca-Cola Company and Social Responsibility in Chile

Over the past 50 years Chile has proven to be a very profitable location for the Coca-Cola Company, with 12 established bottling plants throughout the country (see exhibit 2). As of 2001, Chile had one of the highest per capita consumption rates of Coca-Cola products in the world, following closely behind the United States and Mexico. From 2002-2004 a survey conducted by Hill and Knowlton Captiva,, La Tercera newspaper, and Collect Market Investigations ranked Coca-Cola de Chile as having the best overall corporate reputation (see exhibit 3). In March 1992, Coca-Cola de Chile created the Coca-Cola Chile Foundation (CCFCH) as a way to channel corporate donations in education. Coca-Cola enjoys a relatively friendly corporate environment in Chile (Herrera 2-4).

Beginning in the 1980s and 90s multinational corporations (MNC), including Coca-Cola became increasingly concerned with corporate social responsibility (CSR). Corporate scandals, public outcry, and grassroots movements calling for corporate accountability brought negative attention to companies like Coca-Cola. These movements also challenged (and continue to challenge) the image Coca-Cola had been projecting of itself; they pointed out contradictions in the corporate narrative. One response to public pressure has been the incorporation of social responsibility into corporate branding strategies as an attempt to rescue the corporate image.

The corporate branding trend began in the 1980s and advocated the marketing of a corporate image alongside a product. Ideally the image was supposed to represent the abstract essence of a corporation. As Naomi Klein explains, “think of the brand as the core meaning of the modern corporation, and of the advertisement as one vehicle used to convey that meaning to the world” (5). Yet, the purpose of this MA project is not to assess the success or failure of Coca-Cola’s corporate branding strategies or their social responsibility campaigns, but to attempt to understand how Coca-Cola processes regional differences and incorporates them into micro-organizational strategies by focusing on ad campaigns and social responsibility initiatives. One way to understand how Coca-Cola digests messages from international campaigns calling for corporate accountability would be to focus on four sites of Coke public relations campaigns: the local, national, regional, and global. Alongside these four sites I also hope to analyze how Coca-Cola is straddling the public and private spheres.

This MA project will attempt to explore how the Coca-Cola Company processes differences in culture, local and national institutions, foreign policy, and other factors that contribute to a country’s unique social/economic environment and uses that information to create a ‘socially responsible’ corporate image. My main arguments thus far are (which are subject to review and revision following in depth research):

1.) Corporate ‘social responsibility’ campaigns have allowed corporations, like Coca-Cola to create new relationships with powerful NGOs and institutions. These campaigns created new locations for corporate advertising and have increased corporate encroachment into the private sphere. Coca-Cola has used the socially responsible image as a tool to attempt to leverage themselves in the global economy, to enforce/reinforce relationships that secure their hegemony, and to discredit organizations that threaten their status.

2.) The Coca-Cola Company does not have a specific or consistent global vision for social responsibility, but instead creates (or neglects to create) a socially responsible image tailored to the location in which it is operating. There is some synchronization between international, regional and local campaigns, but there are inconsistencies in the overall coordination.

3.) The Coca-Cola Company relies heavily upon corporate sanctioned studies, technology, and institutions to create an image of social responsibility. This ‘top down’ approach serves three main functions: first, to gain specific information about the local environment which is incorporated into a micro-organizational strategy; secondly, it serves as a mechanism to co-opt and control local discourses on social responsibility; and third Coca-Cola is able to position themselves (amongst various institutions) as a moral authority.

4.) The image of a ‘socially responsible’ corporation is used as a tool to distract from unethical international corporate practices, as a way to discredit ‘grassroots’ organizations calling for corporate accountability, as a way to cultivate a set of values that benefit Coca-Cola, and as part of a preemptive plan to counter any accusations of human rights abuses/unethical business practices.

Proposed Methodology

My research will mainly entail analysis of material on the Coca-Cola Company’s website and the Coca-Cola de Chile website including corporate documents describing corporate structure and practices (e.g. ‘The Coca-Cola Management System’) to gain a sense of the Company’s managerial style and to compare social responsibility PR material (e.g. does social responsibility PR appear the same on the Chile site as on the US site?). It will also involve analyzing television advertisements aired in Chile, in Latin America and internationally to understand how Coca-Cola is marketing social responsibility. Finally, I will analyze material put out by organizations part of an international campaign to hold Coca-Cola accountable including SINALTRAINAL, India Resource Center, and Human Rights Watch to understand how the Coca-Cola Company utilizes a socially responsible image to discredit/challenge their campaigns. The analysis of anti-Coke material put out by international campaigns will provide insight into how Coca-Cola’s image is being challenged on the global level and to see how those campaigns are resonating and/or not resonating in Coca-Cola’s social responsibility PR material in Chile and Latin America.

George Gerbner in “Telling Stories, or How Do We Know What We Know?” discusses a ‘three-pronged research approach’ to analyzing media. The first step is “institutional process analysis” which calls for researching the formation of policies surrounding the flow of media messages. The second step entails “message system analysis” or analyzing the content of stories and messages in the media. The third step is “cultivation analysis” which mostly consists of polling light and heavy viewers of television to gauge the cultural effects of media. At the foundation of Gerbner’s approach is ‘cultivation theory’ or the idea that the media shapes a viewer’s conception of social reality and ‘cultivates’ a set of beliefs or values. As Gerbner explains, “the heart of the analogy of television and religion, and the similarity of their social functions, lies in the continual repetition of patterns (myths, ideologies, "facts", relationships, etc.), which serve to define the world and legitimize the social order” (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, Signorielli, 1986).

Gerbner’s ‘cultivation theory’ will orient my analysis. I will approach advertising as a medium to convey and potentially cultivate a set of values and beliefs about social reality. What beliefs and values are behind the stories told in Coke ads? What do they say about race, class and gender? Although Gerbner called for an empirical analysis of media, including polling TV viewers, I will focus my MA project on analyzing the framework of Coca-Cola’s advertising strategy (e.g. How do they gain access to schools, tv, sports events, etc?) as well as the underlying messages in their advertising strategy (e.g. Who are they targeting? What are their techniques? What do the ads convey about race, class and gender?).

Proposed Questions

1.) How does Coca-Cola manage its image and operations between and within the public and private sphere?

2.) What value systems are enforced/reinforced in Coca-Cola ads aired in Chile and Latin America? What messages do the ads convey about race, gender, and class?

3.) What do the Coca-Cola advertisements in Chile reveal about the company’s understanding (or misunderstanding) of culture, local/national institutions, and foreign policy?

4.) How are they attempting to incorporate an image of social responsibility into their advertisements and branding strategy in Chile? What are the motives? Do US-based and international campaigns against Coca-Cola have any impact on local, national, regional, and international ad campaigns? Why? Why not? What are the differences between how they market themselves in Chile versus marketing geared towards Latin America or the international community?

5.) How do Coca-Cola ad campaigns focused on social responsibility attempt to co-opt and/or reorient international/national/local dialogues on corporate accountability and ethical behavior in general? In Chile, Coca-Cola channels most of their corporate donations into education- how do they benefit from this approach? What are the intended and unintended consequences of the Coca-Cola Chile Foundation?

6.) What are the intended/unintended consequences of how Coke navigates corporate social responsibility in Chile? How does it avoid having to do social responsibility campaigns in Latin America and/or Chile? Why? Why not?

7.) Are there holes in the coordination between local, national, regional and international social responsibility campaigns? What corporate weaknesses do they reveal?

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(29)

-

▼

January

(23)

- MA Theis Draft Proposal 08/18/08

- Annotated Bibliography

- Notes On Coca-Globalization, by Robert Foster

- Press Release: CCC Joins Business Leaders Initiati...

- Press Release: CCC Releases Annual Corporate Respo...

- Business Profile, Corporate Responsibility Review ...

- Press Release: Coca-Cola Annual Environmental Repo...

- Colombia and India Updates, Corporate Responsibili...

- Aguilas Negras (Black Eagles), May 1, 2008

- About the Coca-Cola Company, The Coca-Cola Quality...

- "Our America" Coca-Cola Educational Material, 1940s

- Chilena Andina se expande en Brasil, 2004

- El Diario Financiero, Interview Coca Cola Chile's ...

- Coca-Cola Quality Management System, 2008

- The World of Coca-Cola, Corporate Museum, Atlanta, GA

- CCC: 'Toward Sustainability: 2004 Citizenship Report'

- Response to India, CR Report, 2006, p18

- Response to Colombia, CR Report, 2006, p17

- Workplace Goals & Progress, CR Review, 2006, p14

- Manufacturing Process, Corporate Responsibility Re...

- Coca-Cola Ad, Chile

- Joint Hearing on Colombia & U.S. Multinationals, p...

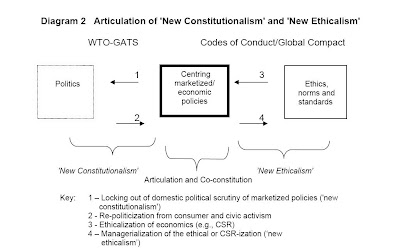

- Diagram 2 from "Articulation of 'New Constitutiona...

-

▼

January

(23)

Friday, January 30, 2009

Thursday, January 29, 2009

Annotated Bibliography

Proposed MA Reading List

1. Items related directly to the project;

Allen, Frederick. Secret Formula: How Brilliant Marketing and Relentless Salesmanship

Made Coca-Cola the Best-Known Product in the World. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publisher, 1994. Allen gives a historical overview of Coca-Cola marketing campaigns from their inception in 1886 until the early 1990s. His book includes detailed accounts of Coca-Cola’s political maneuvering within the U.S. and abroad, providing insight into how Coca-Cola has managed potential crises.

Frederick Allen is an author and a journalist. He has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. His books include Secret Formula (1994) and Atlanta Rising: the Invention of an International City, 1946-1996 (1996).

“Cementos Bio-Bio, CTI, Los Productores de Salmon y Coca-Cola Chile Obtuvieron

Premios Sofofa 1999.” Comunicado de Prensa. 11 Noviembre 1999.This press release is from Sofofa, a Chilean Industrial Federation that promotes the interests of Chilean industry and business. The statement includes details on the TAVEC laboratories set up and funded by the Coca-Cola Company via la Fundación Coca-Cola Chile. The TAVEC labs are one component of Coca-Cola’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) campaign in Chile.

The Coca-Cola Company. June 2008.

This is the Coca-Cola Company website intended for a U.S. audience. It contains financial statements, company reports, press releases, advertisements, statements from the CEO, and company descriptions of CSR campaigns. The annual stockholder’s meeting is also available from their website for about a month after the meeting. The material on the U.S. based website will be compared with the websites intended for Chilean and Colombian audiences to analyze differences in material on CSR campaigns.

Coca-Cola de Chile. August 2008.This is the Coca-Cola website intended for a Chilean audience and includes interactive advertising campaigns like the “Movimiento Bienstar” and “El Lado Coca-Cola de la Vida.” As mentioned above, the material contained on this website will be compared with material on the U.S. and Colombian Coca-Cola websites.

The Coca-Cola Company. The Coca-Cola Management System. 28 March 2008. This

document outlines Coca-Cola’s management strategy and includes sections on “Incident Management and Crisis Resolution (IMCR)” and “Consumer Response and Customer Satisfaction.” It also describes Coca-Cola as “a responsible citizen of the world.” Herrera, in the article below, describes the Coca-Cola system as “the relationship of the Coca-Cola Company, bottlers, plants and distribution territories” (71). It will be treated as a primary source to gain insight into Coca-Cola’s operational strategy from a corporate perspective.

The Coca-Cola Company. The Coca-Cola Quality System. June 2008.

< http://www.thecoca-colacompany.com/ourcompany/quality_brochures.html> Another version of the Coca-Cola Management System is available online via the Coca-Cola website. This document will be compared with the above document “The Coca-Cola Management System” to see if there are significant differences. The Coca-Cola website also includes corporate statements on quality, the environment, safety, and supplier expectations. One section entitled “Keeping Our Promise: Environment” outlines how Coca-Cola manages their environmental impact. Further research will need to be done to see how Coca-Cola is implementing their outlined proposal, especially in areas where there are environmental concerns (e.g. El Salvador, India).

The Coca-Cola Company. United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form

10-K. 28 February 2008. < http://ir.thecoca-colacompany.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=94566&p=IROL-sec&control_selectgroup=Annual%20Filings> Coca-Cola’s 10-K form outlines their basic operations within the U.S. and internationally. The statement includes legal descriptions of bottler’s and distribution agreements, ownership interests (e.g. Coca-Cola Enterprises Inc. and Coca-Cola FEMSA), corporate risk factors, and legal proceedings.

Coca-Cola Embonor S.A. August 2008.

There are three major Coca-Cola bottlers and distributors in Chile; Embotelladora Andina S.A., Coca-Cola Embonor S.A., and Coca-Cola Polar S.A. The Coca-Cola Company, based in the U.S., has ownership interests in all three. This website is for Coca-Cola Embonor S.A. and is specifically targeted to 35% of the Chilean market, as well as parts of Bolivia including Región de Arica-Parinacota, Región de Tarapacá, Región de Valparaíso, Región del Maule, Región del Bío Bío, Región de la Araucanía, Región de los Ríos, Región de los Lagos, Región del Libertador General Bernardo O’Higgins. This website includes information about Coca-Cola Embonor S.A. operations, CSR campaigns, and financial statements.

Coca-Cola Television Advertisements. “Fifty Years of Coca-Cola Television

Advertisements: Highlights from the Motion Picture Archives at the Library of Congress.” The Library of Congress. 29 November 2000.

The Library of Congress houses about 5 decades worth of Coca-Cola commercials. The commercials aired internationally, within Latin America, Colombia, and Chile will be analyzed to understand how Coke is gearing advertisements to different regions of the international market. Analysis will be focused on themes surrounding race, class, and gender, as well as any references to CSR campaigns.

Foster, Robert. Coca-Globalization: Following Soft Drinks from New York to New

Guinea. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd., 2008. Foster explores the social life of Coca-Cola in a number of settings, focusing primarily on Papua New Guinea. Beverages are used as an entry point to discuss the various types of social and cultural exchanges occurring within an increasingly interconnected world. The book is divided into two parts; ‘Soft Drinks and the Economy of Qualities’ and ‘Globalization, Citizenship and the Politics of Consumption.’ Of particular importance is Foster’s attention to how individuals ascribe different social and cultural meanings to commodities like Coca-Cola. Foster is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Rochester.

Gill, Lesley. “Labor and Human Rights: ‘The Real Thing’ in Colombia.” Report to the

Human Rights Committee of the American Anthropological Association, November 2004.Gill prepared this report on Coca-Cola’s operations in Colombia for the Human Rights Committee of the American Anthropological Association (AAA) to encourage the AAA to take a position on the international boycott of Coca-Cola products. The report focuses on the history of anti-union violence in Colombia, including the violence experienced by members of SINALTRAINAL, the union representing Coca-Cola workers in Colombia.

Herrera, Jorge. “Coca-Cola Chile Foundation.” Harvard Business Publishing, Social

Enterprise Knowledge Network (December 2005): 1-18. Herrera gives a historical account of how the Coca-Cola Chile Foundation (CCCF) was established in 1992 and some general background on Coca-Cola’s operation in Chile. He provides a list of CCCF board members, a map of geographical territories, and financial donations. The article gives an overview of the mission and scope of the CCCF, the main example of Coca-Cola’s CSR campaign in Chile. Herrera is a professor at La Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and worked for Coca-Cola as Gerente de Planificación y Desarrollo de Coca-Cola Embonor S.A.(Director of Planning and Development).

Hutt, Peter Barton. “The Image and Politics of Coca-Cola: From Early Years to Present.”

Leda at Harvard Law School.16 April 2001.Professor Peter Barton Hutt oversaw this combined class paper at Harvard Law School available online. The paper gives a historical overview, highlighting how Coca-Cola navigated potential crises in the U.S, Israel, South Africa, Guatemala, France, Germany, Nigeria, and Mexico. Of particular significance is the author’s insight into Coca-Cola’s management of the crisis in Guatemala. He comments on the company’s initial response, where they claimed they had no involvement in or knowledge of the murder of union leaders. The author states, “Their detachment from a bottler’s activities, even if laws of human rights have been violated, is conspicuously inconsistent with the company’s obsession with overseeing local production and promotion.” According to the author’s perspective, employees of the Coca-Cola Corporation are highly involved with marketing on the local level, but remove themselves from situations where they could be held legally liable for serious workers’ rights or human rights’ violations.

Kay, Julie. “11th Circuit Asked to Clarify Corporate Liability.” Daily Business Review.

30 October 2006.

Kay discusses the lawsuit brought by the United Steelworkers Union and the International Labor Rights Fund on behalf of SINALTRAINAL against the Coca-Cola Company. Kay focuses on the interpretation of the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA), the statute allowing foreign claimants to “bring suit in a U.S. court for any violation of ‘the law of nations.’” The ATCA is being used by SINALTRAINAL to attempt to hold Coca-Cola accountable for human rights violations committed in Colombia. Judge Martinez, the judge presiding over the Coca-Cola case, asked for further clarification of the ATCA from a federal appeals court (11th Circuit). The lawsuit is one example of contestations to Coca-Cola’s operations in Colombia.

“Laboratorio Coca-Cola TAVEC Fundación Coca-Cola Chile.” Amcham Chile. 17

Augusto 2008.This news article covers the Coca-Cola Chile Foundation (CCCF), including the TAVEC labs. According to the article, the CCCF has invested more than $7 million in education 3 years. The estimated social impact is outlined and a personal testimony from a student is given at the end of the article. The article will provide background information on the CCCF and will also serve as an example of how Coca-Cola markets their CSR campaigns in Chilean newspapers.

Pendergrast, Mark. For God, Country and Coca-Cola: The Definitive History of the Great American Soft Drink and the Company that Makes It. New York, NY: Basic

Books, 2000. Pendergrast provides an overview of Coca-Cola’s operations that is more thorough than Allen’s Secret Formula. Pendergrast, primarily an investigative journalist, goes beyond the manifest meaning of the Coca-Cola aesthetic to ask more complex questions about Coke’s business practices from a journalistic and historical perspective. Pendergrast includes accounts of how Coca-Cola has been able to navigate tumultuous political waters and describes some of Coca-Cola’s first markets in Latin America. His book provides a solid and thorough history of the Coca-Cola Company.

Protection and Money: U.S. Companies, Their Employees, and Violence in Colombia.

Hearing before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on International Organizations, Human Rights, and Oversight and the Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere and House Committee on Education and Labor Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor and Pensions and the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, 110th Cong., 1st Sess. (June 28, 2007). The U.S. Congress organized a hearing on the presence of U.S. multinationals in Colombia after Chiquita admitted to paying paramilitaries about $1.7 million over the course of seven years (between 1997-2004). The hearing includes testimony from members of the Colombian military, including Edwin Guzman. Guzman protected Drummond property and testified that “the AUC and the Colombian military shared the opinion that unions in general, and the union at Drummond in particular, represented a subversive organization and consequently a legitimate military target.” The hearing includes first hand accounts of the situation in Colombia, highlighting how U.S. multinationals, the Colombian military and paramilitary forces (AUC) work hand in hand to suppress union power.

Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Industria de Alimentos (SINALTRAINAL).

Agosto 2008.SINALTRAINAL is the Colombian union currently involved in a lawsuit with the Coca-Cola Company. The lawsuit accuses employees of the Coca-Cola Company of colluding with paramilitary forces leading to the torture, murder and intimidation of union members, including the murder of Isidro Segundo Gil. The website has a copy of SINALTRAINAL’s manifesto on the campaign against Coca-Cola, as well as an archive of other documents and press releases put out by SINALTRAINAL. The website provides information about active contestations to Coca-Cola’s practices in Colombia.

United States. House of Representatives. Committee on International Relations. The

Global Water Crisis: Evaluating U.S. Strategies to Enhance Access to Safe Water and Sanitation. 29 June 2005. 109th Cong., 1st sess.In June 2005, the Committee on International Relations organized a hearing on the global water crisis. The Committee received testimonies from members of the United Nations Children’s Fund, the UN Development Program and a number of government and NGO personnel. One program that was highlighted during the hearing was the Community Watershed Partnership, which is a campaign involving USAID, the Coca-Cola Company, and the Global Environmental and Technology Foundation. The campaign is an example of a CSR initiative geared for an international audience and illustrates Coca-Cola’s engagement with governmental and non-governmental agencies.

2. Items related to the background areas around the project

Bauer, Carl J. Against the Current: Privatization, Water Markets, and the State in Chile.

Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1998. Bauer focuses his study on how radical free-market economics and privatization has impacted water management. His analytical framework incorporates political, economic, legal, and environmental perspectives which he argues, “come together in property rights” (7). Bauer’s findings are centered around extensive interviews conducted over the course of two and a half years. Coca-Cola relies heavily on water for the production of its beverages. Building off of Bauer’s study, I would like to explore how water privatization has helped create a corporate friendly environment for the Coca-Cola Company.

Chomsky, Aviva. Linked Labor Histories: New England, Colombia, and the Makings of a

Global Working Class. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. Chomsky provides an alternative interpretation of the current political and economic trends under globalization. By examining the connections between labor histories in New England and Colombia she argues that the power of the nation-state is not diminishing in the new era of globalization, but instead nations are being pulled between two forces; the demands of capital and pressure from popular movements. The book is divided into two sections on New England and Colombia. Connections between the two locations are drawn around themes of migration, labor-management collaboration, and the flexibility of capital. Chomsky highlights the role of U.S. multinational corporations in shaping Colombia’s labor history. She also briefly discusses the Stop Killer Coke campaign, as one example of contentious labor movements against U.S. corporations.

Gwynne, Robert N. and Cristóbal Kay, ed. Latin America Transformed: Globalization

and Modernity. New York; Oxford University Press, 2001. Gwynne and Kay present the current theoretical debates surrounding globalization from a political economy perspective. Theories on globalization are elaborated throughout the book by various authors. Divided into seven parts, each essay discusses a different aspect of the transformations occurring within Latin American society including changes in resource management, migration patterns, labor, and gender relations. Each author traces the trajectory of significant shifts in political, economic and social relations in Latin America.

May, Christopher. Global Corporate Power. Boulder, CO: Lynne Riener Publishers,

2006. This book is a collection of essays on multinational corporations within the contemporary context, where MNCs wield increasing economic, political and social might. The third section of the book is focused on the theme of corporate social responsibility and addresses the evolution of corporate citizenship, as well as the growth and significance of corporate social responsibility campaigns. Pegg challenges the effectiveness of CSR campaigns stating, “As long as the overall ordering principle remains self-interested profit maximization within a capitalist economic system, we should not expect firm-level variations in CSR strategies to produce significant overall differences in outcomes” (268). Pegg succinctly argues that the nature of capitalism places limitations on the scope of CSR campaigns.

Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. “How Politics Trumped Truth in the Neo-Liberal

Revision of Chile’s Development.” Discussion paper, September 2006.In response to dominant discourses about Chile as a shining model of neoliberal economic reform, Public Citizen’s Trade Watch published this discussion paper to outline the contradictions in the neoliberal rhetoric. The paper highlights three main problems with the current model including economic disparities in wealth, the reliance on the export of limited resources, and cuts to social services like education and health care. They suggest that countries implement non-neoliberal policies instead of the neoliberal policies prescribed by the WTO, IMF and FTA. This paper gives an economic snapshot of Chile and a brief overview of the impacts of neoliberal economic policies.

Roberts, John. “Corporate Governance and the Ethics of Narcissus.” Business Ethics

Quarterly. 11.1 (January 2001): 109-127. Roberts deconstructs current notions of business ethics drawing the distinction between being ‘seen to be ethical’ and ‘being responsible for.’ He argues that the act of being seen as ethical and the obsession with projecting an ethical self image is markedly different than the sense of responsibility that comes with the recognition of others. Self-obsessed and narcissistic behavior is encouraged within typical business environments, including the “progressive instrumentalization of relationships” where others are viewed as vehicles to either leverage or limit the ultimate realization of the self. His insights into the nature of ethical trends within business circles will be incorporated into discussions of the limitations of CSR campaigns and the nature of corporate culture.

Silva, Eduardo. The State and Capital in Chile: Business Elites, Technocrats, and Market

Economics. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996. Silva argues that economic elites in Chile played a larger role in constructing Chile’s economic policies and influencing the shift from import substitution industrialization to free market economics than previously thought. He states, “this study shows how state structure and international factors influenced intracapitalist and landowner conflict and, hence, coalition formation over different policy periods” (3). An overview of what historical forces and class alliances have laid the economic groundwork for the contemporary moment will aid understanding of Coca-Cola’s current success in Chile. I also anticipate that similar class alliances have catapulted the Coca-Cola Company into a highly respected position amongst Chilean consumers.

Winn, Peter, ed. Victims of the Chilean Miracle: Workers and Neoliberalism in the

Pinochet Era, 1973-2002. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004. In this edited collection of essays, the authors trace the impacts of the dictatorship and neoliberal economic policies on women, labor, and the environment from 1973-2002. Stillerman examines the plight of organized labor by focusing on the workers at Madeco, a copper manufacturer. Under Pinochet, the owners and managers attempted to dismantle the union through harsh repression, various management schemes, and more subtle disciplinary tactics. Although unionism was shaken during those years, the neoliberal reforms gave way to new forms of class conscious identity focused partially on anti-consumerism. Stillerman explains, “union members have developed a complicated set of ideas and behaviors in response to work intensification and new forms of debt-financed consumption” (181). Stillerman explains how unions are reacting to the increase presence of international consumer goods (primarily from the U.S.), debt financing, and ‘cultural imperialism.’

3. Items about theory and method necessary for research on the project

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and

Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso, 1991. Anderson counters claims that the nation state is dead by arguing that “nation-ness is the most universally legitimate value in the political life of our time” (3). He also offers a complex conceptualization of the nation as an imagined community and asserts that “communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined” (6). Appadurai (1996) relates the definition of imagined communities to the power of consumer culture and discussions of consumption. He states “thus in creating experiences of losses that never took place, these advertisements create what might be called ‘imagined nostalgia,’ nostalgia for things that never were” (77). Advertising campaigns have tapped into the powerful instruments of nationalism and consumer imagination, as a way to cultivate product loyalty.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization.

Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996. Appadurai dives into modernization as a cultural experience, starting with the wholly personal aspects of modernization and then progressing towards the theoretical, tying the intimate and the abstract eloquently together throughout the book. He uses the themes of media and migration to explore their “joint effect on the work of the imagination as a constitutive feature of modern subjectivity” (3). His discussion of consumption in Chapter 4 is particularly relevant for a discussion on Coca-Cola’s social and cultural impact. He argues that “the aesthetic of ephemerality becomes the civilizing counterpart to flexible accumulation” expanding previous interpretations by Weber and Campbell of pleasure and satisfaction as the “organizing principle of modern consumption” (85). Appardurai explains how ephemerality is able to capture the imagination of consumers.

Crehan, Kate. Gramsci, Culture and Anthropology. Berkley, CA: University of California

Press, 2002. Crehan walks the reader through Gramsci’s work, grounding it in an anthropological perspective and clarifying some of the more complex Gramscian concepts. In Chapter 6 Crehan focuses on the production of culture, she states “the production and reproduction of culture is at the heart of what intellectuals do… it is they who produce the broad cultural conceptions of the world that underpin particular power regimes” (156). I hope to explore the role of the multinational corporation in the creation of culture. Gramscian theory provides an ample foundation from which to approach the increasingly complex dialectical relationship between civil society and corporate marketing campaigns.

Cultural Anthropology. “The Coke Complex.” Journal of the Society for Cultural

Anthropology, 22.4 (November 2007). In response to Leslie Gill’s report on human rights violations in Colombia and the AAA’s call for the boycott of Coca-Cola products, the editors of Cultural Anthropology decided to issue a call for papers on the “Coke Complex.” They describe the “Coke Complex” as “the multiplicity of beliefs, practices, organizational forms, and politicoeconomic dynamics that enable and index The Coca-Cola Company” (616). One article of particular interest is entitled “The Work of the New Economy: Consumers, Brands, and Value Creation” in which Foster focuses on the "merger between science studies and economic sociology" to understand the process of brand creation. He argues that corporate externalities include the emergence of 'publics' that have expanded in spatial scale and include a growing diversity of economic actors. He hones in on the sites of current and potential contestation which, in the current economic moment, include social relations built around commodities. Since the very nature of brands places a lot of potential value in public space there is a high potential for effective and powerful contestation.

Ehrenberg, John. Civil Society: The Critical History of an Idea. New York, NY: New

York University Press, 1999. Ehrenberg traces the theoretical history of civil society through three main traditions. He describes the first tradition as the conceptualization of civil society as “a politically organized commonwealth” (xi). The concept shifts to encompass “private property, individual interest, political democracy, the rule of law, and an economic order devoted to prosperity” (xiii). The third shift envisioned civil society as a regulatory force or as “a community whose solidarity reconciled the subjectivity of individual interests with the objectivity of the common good” (xiv). By outlining the evolution of theories on civil society, Ehrenberg is able to articulate their limitations and ultimately call for a reconceptualization of the term in light of current social realities. He emphasizes the need to consider micro and macro forces in any discussion of civil society stating “powerful states and invasive markets constitute and penetrate a civil society whose ability to mediate depends as much on the environment in which it sits as on its own intrinsic strength” (232).

Evans, Jessica and Stuart Hall. Visual Culture: The Reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications Inc., 2005. Visual Culture is a collection of essays on culture and visuality divided into three parts. Evans and Hall turn the reader’s attention to five components of the image; “visuality, apparatus, institutions, bodies and figurality” (4). By understanding the complex relationship between these components, one can begin to understand the impact of an image. Parts I and III are particularly relevant for this MA project because they focus on ‘cultures of the visual’ and ‘looking and subjectivity.’ These essays provide a basis from which to engage the latent content in advertisements.

Gereffi, Gary and Miguel Korzeniewicz. Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994. Gereffi and Korzeniewicz discuss the concept of global commodity chains (GCC) which they define as “sets of interorganizational networks clustered around one commodity or product, linking households, enterprises, and states to one another within the world economy” (2). They suggest that the concept of GCC will help to theoretically connect ‘macro-historical concerns’ with ‘micro-organizational and state-centered’ issues. The GCC model makes it easier to visualize the various components of a multinational corporate structure dispersed around the world. Gereffi and Korzeniewicz also explicate some of the forces driving corporate structuring and restructuring.

Hale, Charles R. Más Que Un Indio: Racial Ambivalence and Neoliberal

Multiculturalism in Guatemala. Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of American Research Press, 2006. Hale argues that multiculturalism is not antithetical to the development or growth of neoliberal ideals. His study focuses on communities in Chimaltenango, Guatemala and more specifically, the Maya rights movement. According to Hale, “proponents of neoliberal governance reshape the terrain of political struggle to their advantage, not by denying indigenous rights, but by the selective recognition of them” (35). Hale’s notion of ‘neoliberal multiculturalism’ is useful for understanding the cultural transformations taking place under neoliberalism.

Jhally, Sut. The Spectacle of Accumulation: Essays in Media, Culture & Politics. New

York, NY: Peter Lang Publishers, 2006. This book contains a collection of essays and interviews on the general themes of media, culture, and advertising. Jhally’s main argument is that current forms of media, which are mostly owned and operated by private interests, promote a culture that is antithetical to democracy. Jhally approaches image analysis from a critical perspective uncovering themes that reflect the interest of a wealthy minority, instead of reflecting the sentiments of a broader majority. His insights on advertising and image of analysis will inform my examination of Coca-Cola ads.

Klein, Naomi. No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies. New York: Picador, 2000.

Klein outlines a major shift in contemporary marketing from a product focused approach to an image focused appraoch (branding). In this context, the brand is the main symbol of capitalism in the global era. Klein also details the brand’s encroachment into public and private spaces, exploring the social and cultural affects, as well as reactions to increased corporate presense in daily life. By exploring the specific techniques of certain brands (e.g. Nike, Pepsi, Disney), Klein draws attention to the co-optation of various cultural niches as a way to expand markets. She discusses the incorporation of feminist, punk, alternative and multicultural aesthetics as a way to appeal to a wider audience. Chapter 4 focuses on the branding of education and uses Coca-Cola as one of the case studies. This book provides a comprehensive history of branding and brings to light some of the social and cultural impacts of branding campaigns.

Paley, Julia. Marketing Democracy: Power and Social Movements in Post-Dictatorship Chile. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. Paley explores notions of democracy by focusing on the health group Llareta within the context of post-dictatorship Chile. Paley examines “how power is exercised in political democracy, particularly through the use of public opinion polls, pressure for grassroots organizations to “participate” by providing social services, and technocratic decision making that excludes the poor” (3). These more subtle forms of state power work to control and contain dissent through processes of coercion and co-optation. Paley likens these methods to a “kind of governmentality” (3). The Coca-Cola Chile Foundation was established to award scholarships and grants to students and high schools within Chile. Yet, Paley’s book raises questions about how state (or non-state) institutions set up with the intention of addressing social problems can become instruments of social discipline.

Smith, Gavin. “Hegemony.” in A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics ed. by David Nugent and Joan Vincent. Blackwell Publishing, 2006: pp216-230. Smith situates the term hegemony within the context of a neoliberal world. Building off Gramsci, Smith calls for the study of how the state, civil society, and the economy constitute fields of power. He states, “a more fruitful exercise would be to try to understand how market discourses, various expressions of the “culture of capitalism”…and the structural features of contemporary capitalism are all interwoven within and between particular sites temporally understood in terms of historical conjectures” (225). With Smith’s suggestions in mind, this MA project aims to incorporate how the circulation and consumption of Coca-Cola relates to culture and cultural processes within the structural framework of the neoliberal economic moment.

1. Items related directly to the project;

Allen, Frederick. Secret Formula: How Brilliant Marketing and Relentless Salesmanship

Made Coca-Cola the Best-Known Product in the World. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publisher, 1994. Allen gives a historical overview of Coca-Cola marketing campaigns from their inception in 1886 until the early 1990s. His book includes detailed accounts of Coca-Cola’s political maneuvering within the U.S. and abroad, providing insight into how Coca-Cola has managed potential crises.

Frederick Allen is an author and a journalist. He has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. His books include Secret Formula (1994) and Atlanta Rising: the Invention of an International City, 1946-1996 (1996).

“Cementos Bio-Bio, CTI, Los Productores de Salmon y Coca-Cola Chile Obtuvieron

Premios Sofofa 1999.” Comunicado de Prensa. 11 Noviembre 1999.

The Coca-Cola Company. June 2008.

This is the Coca-Cola Company website intended for a U.S. audience. It contains financial statements, company reports, press releases, advertisements, statements from the CEO, and company descriptions of CSR campaigns. The annual stockholder’s meeting is also available from their website for about a month after the meeting. The material on the U.S. based website will be compared with the websites intended for Chilean and Colombian audiences to analyze differences in material on CSR campaigns.

Coca-Cola de Chile. August 2008.

The Coca-Cola Company. The Coca-Cola Management System. 28 March 2008. This

document outlines Coca-Cola’s management strategy and includes sections on “Incident Management and Crisis Resolution (IMCR)” and “Consumer Response and Customer Satisfaction.” It also describes Coca-Cola as “a responsible citizen of the world.” Herrera, in the article below, describes the Coca-Cola system as “the relationship of the Coca-Cola Company, bottlers, plants and distribution territories” (71). It will be treated as a primary source to gain insight into Coca-Cola’s operational strategy from a corporate perspective.

The Coca-Cola Company. The Coca-Cola Quality System. June 2008.

< http://www.thecoca-colacompany.com/ourcompany/quality_brochures.html> Another version of the Coca-Cola Management System is available online via the Coca-Cola website. This document will be compared with the above document “The Coca-Cola Management System” to see if there are significant differences. The Coca-Cola website also includes corporate statements on quality, the environment, safety, and supplier expectations. One section entitled “Keeping Our Promise: Environment” outlines how Coca-Cola manages their environmental impact. Further research will need to be done to see how Coca-Cola is implementing their outlined proposal, especially in areas where there are environmental concerns (e.g. El Salvador, India).

The Coca-Cola Company. United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form

10-K. 28 February 2008. < http://ir.thecoca-colacompany.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=94566&p=IROL-sec&control_selectgroup=Annual%20Filings> Coca-Cola’s 10-K form outlines their basic operations within the U.S. and internationally. The statement includes legal descriptions of bottler’s and distribution agreements, ownership interests (e.g. Coca-Cola Enterprises Inc. and Coca-Cola FEMSA), corporate risk factors, and legal proceedings.

Coca-Cola Embonor S.A. August 2008.

Coca-Cola Television Advertisements. “Fifty Years of Coca-Cola Television

Advertisements: Highlights from the Motion Picture Archives at the Library of Congress.” The Library of Congress. 29 November 2000.

Foster, Robert. Coca-Globalization: Following Soft Drinks from New York to New

Guinea. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd., 2008. Foster explores the social life of Coca-Cola in a number of settings, focusing primarily on Papua New Guinea. Beverages are used as an entry point to discuss the various types of social and cultural exchanges occurring within an increasingly interconnected world. The book is divided into two parts; ‘Soft Drinks and the Economy of Qualities’ and ‘Globalization, Citizenship and the Politics of Consumption.’ Of particular importance is Foster’s attention to how individuals ascribe different social and cultural meanings to commodities like Coca-Cola. Foster is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Rochester.

Gill, Lesley. “Labor and Human Rights: ‘The Real Thing’ in Colombia.” Report to the

Human Rights Committee of the American Anthropological Association, November 2004.

Herrera, Jorge. “Coca-Cola Chile Foundation.” Harvard Business Publishing, Social

Enterprise Knowledge Network (December 2005): 1-18. Herrera gives a historical account of how the Coca-Cola Chile Foundation (CCCF) was established in 1992 and some general background on Coca-Cola’s operation in Chile. He provides a list of CCCF board members, a map of geographical territories, and financial donations. The article gives an overview of the mission and scope of the CCCF, the main example of Coca-Cola’s CSR campaign in Chile. Herrera is a professor at La Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and worked for Coca-Cola as Gerente de Planificación y Desarrollo de Coca-Cola Embonor S.A.(Director of Planning and Development).

Hutt, Peter Barton. “The Image and Politics of Coca-Cola: From Early Years to Present.”

Leda at Harvard Law School.16 April 2001.

Kay, Julie. “11th Circuit Asked to Clarify Corporate Liability.” Daily Business Review.

30 October 2006.

“Laboratorio Coca-Cola TAVEC Fundación Coca-Cola Chile.” Amcham Chile. 17

Augusto 2008.

Pendergrast, Mark. For God, Country and Coca-Cola: The Definitive History of the Great American Soft Drink and the Company that Makes It. New York, NY: Basic

Books, 2000. Pendergrast provides an overview of Coca-Cola’s operations that is more thorough than Allen’s Secret Formula. Pendergrast, primarily an investigative journalist, goes beyond the manifest meaning of the Coca-Cola aesthetic to ask more complex questions about Coke’s business practices from a journalistic and historical perspective. Pendergrast includes accounts of how Coca-Cola has been able to navigate tumultuous political waters and describes some of Coca-Cola’s first markets in Latin America. His book provides a solid and thorough history of the Coca-Cola Company.

Protection and Money: U.S. Companies, Their Employees, and Violence in Colombia.

Hearing before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on International Organizations, Human Rights, and Oversight and the Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere and House Committee on Education and Labor Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor and Pensions and the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, 110th Cong., 1st Sess. (June 28, 2007). The U.S. Congress organized a hearing on the presence of U.S. multinationals in Colombia after Chiquita admitted to paying paramilitaries about $1.7 million over the course of seven years (between 1997-2004). The hearing includes testimony from members of the Colombian military, including Edwin Guzman. Guzman protected Drummond property and testified that “the AUC and the Colombian military shared the opinion that unions in general, and the union at Drummond in particular, represented a subversive organization and consequently a legitimate military target.” The hearing includes first hand accounts of the situation in Colombia, highlighting how U.S. multinationals, the Colombian military and paramilitary forces (AUC) work hand in hand to suppress union power.

Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Industria de Alimentos (SINALTRAINAL).

Agosto 2008.

United States. House of Representatives. Committee on International Relations. The

Global Water Crisis: Evaluating U.S. Strategies to Enhance Access to Safe Water and Sanitation. 29 June 2005. 109th Cong., 1st sess.

2. Items related to the background areas around the project

Bauer, Carl J. Against the Current: Privatization, Water Markets, and the State in Chile.

Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1998. Bauer focuses his study on how radical free-market economics and privatization has impacted water management. His analytical framework incorporates political, economic, legal, and environmental perspectives which he argues, “come together in property rights” (7). Bauer’s findings are centered around extensive interviews conducted over the course of two and a half years. Coca-Cola relies heavily on water for the production of its beverages. Building off of Bauer’s study, I would like to explore how water privatization has helped create a corporate friendly environment for the Coca-Cola Company.

Chomsky, Aviva. Linked Labor Histories: New England, Colombia, and the Makings of a

Global Working Class. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. Chomsky provides an alternative interpretation of the current political and economic trends under globalization. By examining the connections between labor histories in New England and Colombia she argues that the power of the nation-state is not diminishing in the new era of globalization, but instead nations are being pulled between two forces; the demands of capital and pressure from popular movements. The book is divided into two sections on New England and Colombia. Connections between the two locations are drawn around themes of migration, labor-management collaboration, and the flexibility of capital. Chomsky highlights the role of U.S. multinational corporations in shaping Colombia’s labor history. She also briefly discusses the Stop Killer Coke campaign, as one example of contentious labor movements against U.S. corporations.

Gwynne, Robert N. and Cristóbal Kay, ed. Latin America Transformed: Globalization

and Modernity. New York; Oxford University Press, 2001. Gwynne and Kay present the current theoretical debates surrounding globalization from a political economy perspective. Theories on globalization are elaborated throughout the book by various authors. Divided into seven parts, each essay discusses a different aspect of the transformations occurring within Latin American society including changes in resource management, migration patterns, labor, and gender relations. Each author traces the trajectory of significant shifts in political, economic and social relations in Latin America.

May, Christopher. Global Corporate Power. Boulder, CO: Lynne Riener Publishers,

2006. This book is a collection of essays on multinational corporations within the contemporary context, where MNCs wield increasing economic, political and social might. The third section of the book is focused on the theme of corporate social responsibility and addresses the evolution of corporate citizenship, as well as the growth and significance of corporate social responsibility campaigns. Pegg challenges the effectiveness of CSR campaigns stating, “As long as the overall ordering principle remains self-interested profit maximization within a capitalist economic system, we should not expect firm-level variations in CSR strategies to produce significant overall differences in outcomes” (268). Pegg succinctly argues that the nature of capitalism places limitations on the scope of CSR campaigns.

Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. “How Politics Trumped Truth in the Neo-Liberal

Revision of Chile’s Development.” Discussion paper, September 2006.

Roberts, John. “Corporate Governance and the Ethics of Narcissus.” Business Ethics

Quarterly. 11.1 (January 2001): 109-127. Roberts deconstructs current notions of business ethics drawing the distinction between being ‘seen to be ethical’ and ‘being responsible for.’ He argues that the act of being seen as ethical and the obsession with projecting an ethical self image is markedly different than the sense of responsibility that comes with the recognition of others. Self-obsessed and narcissistic behavior is encouraged within typical business environments, including the “progressive instrumentalization of relationships” where others are viewed as vehicles to either leverage or limit the ultimate realization of the self. His insights into the nature of ethical trends within business circles will be incorporated into discussions of the limitations of CSR campaigns and the nature of corporate culture.

Silva, Eduardo. The State and Capital in Chile: Business Elites, Technocrats, and Market

Economics. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996. Silva argues that economic elites in Chile played a larger role in constructing Chile’s economic policies and influencing the shift from import substitution industrialization to free market economics than previously thought. He states, “this study shows how state structure and international factors influenced intracapitalist and landowner conflict and, hence, coalition formation over different policy periods” (3). An overview of what historical forces and class alliances have laid the economic groundwork for the contemporary moment will aid understanding of Coca-Cola’s current success in Chile. I also anticipate that similar class alliances have catapulted the Coca-Cola Company into a highly respected position amongst Chilean consumers.

Winn, Peter, ed. Victims of the Chilean Miracle: Workers and Neoliberalism in the

Pinochet Era, 1973-2002. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004. In this edited collection of essays, the authors trace the impacts of the dictatorship and neoliberal economic policies on women, labor, and the environment from 1973-2002. Stillerman examines the plight of organized labor by focusing on the workers at Madeco, a copper manufacturer. Under Pinochet, the owners and managers attempted to dismantle the union through harsh repression, various management schemes, and more subtle disciplinary tactics. Although unionism was shaken during those years, the neoliberal reforms gave way to new forms of class conscious identity focused partially on anti-consumerism. Stillerman explains, “union members have developed a complicated set of ideas and behaviors in response to work intensification and new forms of debt-financed consumption” (181). Stillerman explains how unions are reacting to the increase presence of international consumer goods (primarily from the U.S.), debt financing, and ‘cultural imperialism.’

3. Items about theory and method necessary for research on the project

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and

Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso, 1991. Anderson counters claims that the nation state is dead by arguing that “nation-ness is the most universally legitimate value in the political life of our time” (3). He also offers a complex conceptualization of the nation as an imagined community and asserts that “communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined” (6). Appadurai (1996) relates the definition of imagined communities to the power of consumer culture and discussions of consumption. He states “thus in creating experiences of losses that never took place, these advertisements create what might be called ‘imagined nostalgia,’ nostalgia for things that never were” (77). Advertising campaigns have tapped into the powerful instruments of nationalism and consumer imagination, as a way to cultivate product loyalty.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization.

Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996. Appadurai dives into modernization as a cultural experience, starting with the wholly personal aspects of modernization and then progressing towards the theoretical, tying the intimate and the abstract eloquently together throughout the book. He uses the themes of media and migration to explore their “joint effect on the work of the imagination as a constitutive feature of modern subjectivity” (3). His discussion of consumption in Chapter 4 is particularly relevant for a discussion on Coca-Cola’s social and cultural impact. He argues that “the aesthetic of ephemerality becomes the civilizing counterpart to flexible accumulation” expanding previous interpretations by Weber and Campbell of pleasure and satisfaction as the “organizing principle of modern consumption” (85). Appardurai explains how ephemerality is able to capture the imagination of consumers.

Crehan, Kate. Gramsci, Culture and Anthropology. Berkley, CA: University of California

Press, 2002. Crehan walks the reader through Gramsci’s work, grounding it in an anthropological perspective and clarifying some of the more complex Gramscian concepts. In Chapter 6 Crehan focuses on the production of culture, she states “the production and reproduction of culture is at the heart of what intellectuals do… it is they who produce the broad cultural conceptions of the world that underpin particular power regimes” (156). I hope to explore the role of the multinational corporation in the creation of culture. Gramscian theory provides an ample foundation from which to approach the increasingly complex dialectical relationship between civil society and corporate marketing campaigns.

Cultural Anthropology. “The Coke Complex.” Journal of the Society for Cultural

Anthropology, 22.4 (November 2007). In response to Leslie Gill’s report on human rights violations in Colombia and the AAA’s call for the boycott of Coca-Cola products, the editors of Cultural Anthropology decided to issue a call for papers on the “Coke Complex.” They describe the “Coke Complex” as “the multiplicity of beliefs, practices, organizational forms, and politicoeconomic dynamics that enable and index The Coca-Cola Company” (616). One article of particular interest is entitled “The Work of the New Economy: Consumers, Brands, and Value Creation” in which Foster focuses on the "merger between science studies and economic sociology" to understand the process of brand creation. He argues that corporate externalities include the emergence of 'publics' that have expanded in spatial scale and include a growing diversity of economic actors. He hones in on the sites of current and potential contestation which, in the current economic moment, include social relations built around commodities. Since the very nature of brands places a lot of potential value in public space there is a high potential for effective and powerful contestation.

Ehrenberg, John. Civil Society: The Critical History of an Idea. New York, NY: New

York University Press, 1999. Ehrenberg traces the theoretical history of civil society through three main traditions. He describes the first tradition as the conceptualization of civil society as “a politically organized commonwealth” (xi). The concept shifts to encompass “private property, individual interest, political democracy, the rule of law, and an economic order devoted to prosperity” (xiii). The third shift envisioned civil society as a regulatory force or as “a community whose solidarity reconciled the subjectivity of individual interests with the objectivity of the common good” (xiv). By outlining the evolution of theories on civil society, Ehrenberg is able to articulate their limitations and ultimately call for a reconceptualization of the term in light of current social realities. He emphasizes the need to consider micro and macro forces in any discussion of civil society stating “powerful states and invasive markets constitute and penetrate a civil society whose ability to mediate depends as much on the environment in which it sits as on its own intrinsic strength” (232).

Evans, Jessica and Stuart Hall. Visual Culture: The Reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications Inc., 2005. Visual Culture is a collection of essays on culture and visuality divided into three parts. Evans and Hall turn the reader’s attention to five components of the image; “visuality, apparatus, institutions, bodies and figurality” (4). By understanding the complex relationship between these components, one can begin to understand the impact of an image. Parts I and III are particularly relevant for this MA project because they focus on ‘cultures of the visual’ and ‘looking and subjectivity.’ These essays provide a basis from which to engage the latent content in advertisements.

Gereffi, Gary and Miguel Korzeniewicz. Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994. Gereffi and Korzeniewicz discuss the concept of global commodity chains (GCC) which they define as “sets of interorganizational networks clustered around one commodity or product, linking households, enterprises, and states to one another within the world economy” (2). They suggest that the concept of GCC will help to theoretically connect ‘macro-historical concerns’ with ‘micro-organizational and state-centered’ issues. The GCC model makes it easier to visualize the various components of a multinational corporate structure dispersed around the world. Gereffi and Korzeniewicz also explicate some of the forces driving corporate structuring and restructuring.

Hale, Charles R. Más Que Un Indio: Racial Ambivalence and Neoliberal

Multiculturalism in Guatemala. Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of American Research Press, 2006. Hale argues that multiculturalism is not antithetical to the development or growth of neoliberal ideals. His study focuses on communities in Chimaltenango, Guatemala and more specifically, the Maya rights movement. According to Hale, “proponents of neoliberal governance reshape the terrain of political struggle to their advantage, not by denying indigenous rights, but by the selective recognition of them” (35). Hale’s notion of ‘neoliberal multiculturalism’ is useful for understanding the cultural transformations taking place under neoliberalism.

Jhally, Sut. The Spectacle of Accumulation: Essays in Media, Culture & Politics. New

York, NY: Peter Lang Publishers, 2006. This book contains a collection of essays and interviews on the general themes of media, culture, and advertising. Jhally’s main argument is that current forms of media, which are mostly owned and operated by private interests, promote a culture that is antithetical to democracy. Jhally approaches image analysis from a critical perspective uncovering themes that reflect the interest of a wealthy minority, instead of reflecting the sentiments of a broader majority. His insights on advertising and image of analysis will inform my examination of Coca-Cola ads.

Klein, Naomi. No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies. New York: Picador, 2000.

Klein outlines a major shift in contemporary marketing from a product focused approach to an image focused appraoch (branding). In this context, the brand is the main symbol of capitalism in the global era. Klein also details the brand’s encroachment into public and private spaces, exploring the social and cultural affects, as well as reactions to increased corporate presense in daily life. By exploring the specific techniques of certain brands (e.g. Nike, Pepsi, Disney), Klein draws attention to the co-optation of various cultural niches as a way to expand markets. She discusses the incorporation of feminist, punk, alternative and multicultural aesthetics as a way to appeal to a wider audience. Chapter 4 focuses on the branding of education and uses Coca-Cola as one of the case studies. This book provides a comprehensive history of branding and brings to light some of the social and cultural impacts of branding campaigns.

Paley, Julia. Marketing Democracy: Power and Social Movements in Post-Dictatorship Chile. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. Paley explores notions of democracy by focusing on the health group Llareta within the context of post-dictatorship Chile. Paley examines “how power is exercised in political democracy, particularly through the use of public opinion polls, pressure for grassroots organizations to “participate” by providing social services, and technocratic decision making that excludes the poor” (3). These more subtle forms of state power work to control and contain dissent through processes of coercion and co-optation. Paley likens these methods to a “kind of governmentality” (3). The Coca-Cola Chile Foundation was established to award scholarships and grants to students and high schools within Chile. Yet, Paley’s book raises questions about how state (or non-state) institutions set up with the intention of addressing social problems can become instruments of social discipline.

Smith, Gavin. “Hegemony.” in A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics ed. by David Nugent and Joan Vincent. Blackwell Publishing, 2006: pp216-230. Smith situates the term hegemony within the context of a neoliberal world. Building off Gramsci, Smith calls for the study of how the state, civil society, and the economy constitute fields of power. He states, “a more fruitful exercise would be to try to understand how market discourses, various expressions of the “culture of capitalism”…and the structural features of contemporary capitalism are all interwoven within and between particular sites temporally understood in terms of historical conjectures” (225). With Smith’s suggestions in mind, this MA project aims to incorporate how the circulation and consumption of Coca-Cola relates to culture and cultural processes within the structural framework of the neoliberal economic moment.

Notes On Coca-Globalization, by Robert Foster

Foster, Robert. Coca-Globalization: Following Soft Drinks from New York to New Guinea. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd., 2008.

Annotation:

Foster explores the social life of Coca-Cola in a number of settings, focusing primarily onPapua New Guinea University of Rochester

Introduction:

Quotes & Reflections

"Objectively, complex connectivity refers to the empirical linkages being established among diverse and physically separated people through movements of capital, media, and, of course, people themselves... Subjectively, complex connectivity refers to the ways in which these linkages are imagined by the people involved, the way in which an individual person's phenomenal world is extended - or foreshortened" (xiii).

"On the other hand, consumers use the commercial value of their brand loyalty to lobby corporations for a variety of goods and services, the delivery of which was once presumed to be the obligation and function of elected governments in promoting social welfare. The result is a distinctively non-democratic though not always negative form of contested governance in which consumers use their market role to act as citizens while corporations use their resources to act like states." (xix)

"I propose to use Coca-Cola soft drinks as symbols of an uncertain process of global connection in which people everywhere, including Papua New Guinea, give meaning to ordinary consumer commodities - though rarely under circumstances of their own devising" (xix).

"Commodities are thus mutable, and this mutability has been most clearly recognized by anthropologists who regard consumers as agents capable of appropriating commodities for ends not imagined by producers. But this mutability is not infinite, a limitation on consumption most clearly recognized by political economists who highlight the structural inequalities of complex connectivity, including basic inequality of access to consumer commodities" (xix).

"For instance, it is by aligning the perspectives of consumers with those of their own that agents on the supply side of worldly things capture the value of consumers' appropriation and use of a product - a complicated way, perhaps, to unpack the notion of "brand loyalty" (xx).

"After the war [WWII], the company explicitly attempted to fashion itself as a local business wherever it operated, such that all consumers everywhere would recognize Coca-Cola as an artifact of their home, however worldly a thing it might be. This attempt involved not only adjusting advertisements to various local sensibilities, but also using the franchaise system of independent bottlers to reembed the product in local social relations (as well as local supply chains). But the attempt gave way in the 1980s to a new globalizing impulse, one that involved the consolidation of bottlers and the emergence of global advertising" (xx).

Personal Reflections

2.) Important to make the distinction between corporate governance and democratic governance. Public relations and consumer driven campaigns might give the illusion of a democratic structure or that corporations are set up to allow feedback and dialogue, but they are ultimately beholden to their shareholders. This distinction becomes particularly important when corporations start taking on responsibilities that were traditionally carried out by governments. For instance, if a corporation is responsible for a shore cleanup project, there could potentially be less avenues for public input and oversight in the project since the work is not being implemented by public officials (who might be required by law to make the details of the project accessible and transparent).

"The concept... shows that it consists of a sequence of actions, a series of operations that transform it, move it and cause it to change hands, to cross a series of metamorphoses that end up putting it into a form judged useful by an economic agent who pays for it" (7).

** Daniel Miller "key innovation has been to regard consumption as a form of labor or work: practical activity in which people meet an object world that confronts them as external and foreign and through which they fashion objectifications of themselves as social beings recognizable to themselves and to others. Miller thus resolves the existential dilemma of Marx's alienated worker, but in the realm of consumption rather than production" (11).

"It is through consumption work that people - often denied the opportunity to do so in their employment - project and contemplate themselves in an object world of , at least in part, their own making" (11).

"[Coca-Cola is] a master symbol of the consumerist ethic, a pause for self-indulgence" (14).

"Thomas's strategy reminds us that cross-cultural consumption is a multi-directional process or, to anticipate, that meanings and qualifications are being generated by all the agents assembled in a network of production, distribution, and exchange, a commodity or product network" (17).

"there is no guarantee that the intention of the producer will be recognized, much less respected, by the consumer from another culture" (17, quoting David Howes).

"The more completely commodities of exogenous origin are assimilated to a new social setting - perhaps they do not even strike anyone as foreign or out-of-place - the more such settings conceal social relations acting at a distance, much as Marx argued that all commodities conceal the social relations of their production" (18).